Isabelle wrote and recorded her first song ever in the spring of 2020, during lockdown.

At the time, she was a pianist who’d never written lyrics or sung. She’d been studying improvising, composing and jazz with me one-on-one and with friends in a small ensemble at her high school. When the pandemic shut down schools, we took it as an opportunity to explore a different way of making music. Working together, we quickly found a voice for her, dove into lyric writing and experimented with production and recording for a month. “find me” was released on a compilation created by a handful of her classmates, many of whom were also writing their first songs, at the end of the spring.

We spent the summer transcribing and analyzing bebop lines in our lessons, but Isabelle naturally found herself drifting back to songwriting in her spare time. When I asked her what she wanted to spend the fall doing, she was clear: write more. She told me she wanted to create something she could be proud of. Now that she was familiar with the basic process of writing and recording, she wanted to aim higher in both the lyrics and the music.

Isabelle had caught the bug.

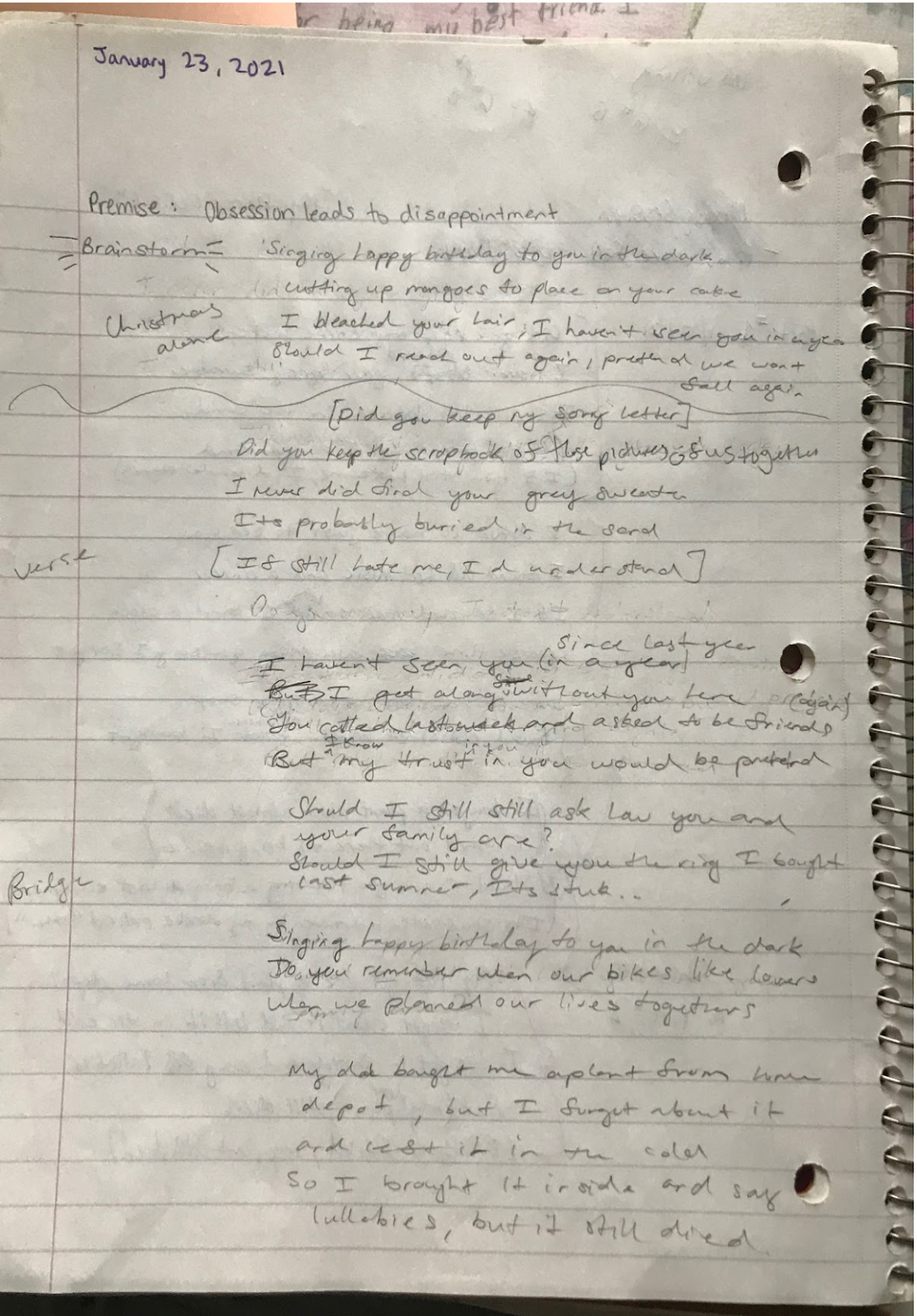

We decided on having her finish a 3-song EP by the new year. In contrast to “find me,” she wanted to keep it absolutely minimal: piano and voice only. Then we started our research. We listened to songs she wanted to emulate and songs that I thought she should hear. We ruthlessly critiqued lyrics, arrangements, and melodies, picking out patterns in her taste and identifying potential pitfalls to avoid. Isabelle started writing, and progress was fast at first. You can see and hear the sorts of fragments she was working with below.

She came up with fifteen ideas like the ones above, which we narrowed down to around five promising candidates. If we could refine three of those into record-worthy material, we’d be set.

We got to work on her top five picks, and the creative process slowed down a bit. We didn't want to create something haphazard—for what Isabelle was going for, we needed to be purposeful about each word and each note. After a few weeks, though, "careful" was starting to become "stuck."

Two types of problems

Every lyric we chose was two-thirds finished, and Isabelle couldn’t decide how to wrap any of them up. She struggled with second-verse curse, or would revamp and reorder lines, only to end up feeling like the lyrics weren’t flowing or making much of an impact. A couple of the songs got near-total rewrites, and still ended up stalled. Every time we looked at a lyric or she played me a sketch, we had the sense something important was missing. This is a normal part of the creative process for every songwriter, but it was the first time Isabelle was running into it, and we were struggling to figure out what the exact nature of the problem was.

Broadly speaking, we tend to run into two types of problems in songwriting and composition. There are conceptual challenges, and technical challenges.

Clichés are often the first things that come to mind when writing. When you overuse them, your lyric feels same-y or boring when you listen back. This is an example of a technical challenge. Other obvious technical challenges exist in our singing, our instrumental technique, or our production chops. These types of problems are resolved by diagnosis and treatment- usually various exercises that you can learn from teachers or books. With practice, they more or less disappear or become very easy to identify and get around.

We get scared of being too vulnerable, so we blunt our language or obfuscate details that would give the song more color and life.

Again, listening back to a song like this is not a terribly satisfying experience. Vulnerability is a conceptual challenge. It’s harder to articulate, and the way forward is deeply personal. You can’t give someone an instruction manual for overcoming an aversion to vulnerability in songwriting. It’s something you learn to do in your own time, and in your own way. Some other conceptual challenges: self-judgment, knowing when something is finished, knowing when something is fresh or raw or fire or whatever you want your music to be.

We lose our focus on the idea or story we’re trying to convey.

You know those conversations you have with teachers or friends where the person speaking isn’t quite sure what point they’re trying to make, and they ramble a bit, and you end up bored or confused? It’s easy for this to happen in songs, because you have very little space to work with. Every word counts, and every line should mean something. It’s all too easy to lose the narrative or emotional thread because of a throwaway line or a good line that belongs in some other song. This kind of problem can be both technical and conceptual. There are simple techniques that can help you structure your ideas, but it’s also about the way you conceive of what a song or story is or can be.

Technical problems can generally be overcome in a matter of months or years. We’re never through with conceptual challenges, and they’re what make music so much fun—we can always rethink them and approach our music from a new angle. At the same time, that depth makes them challenging to grapple with when we first encounter them in the wild.

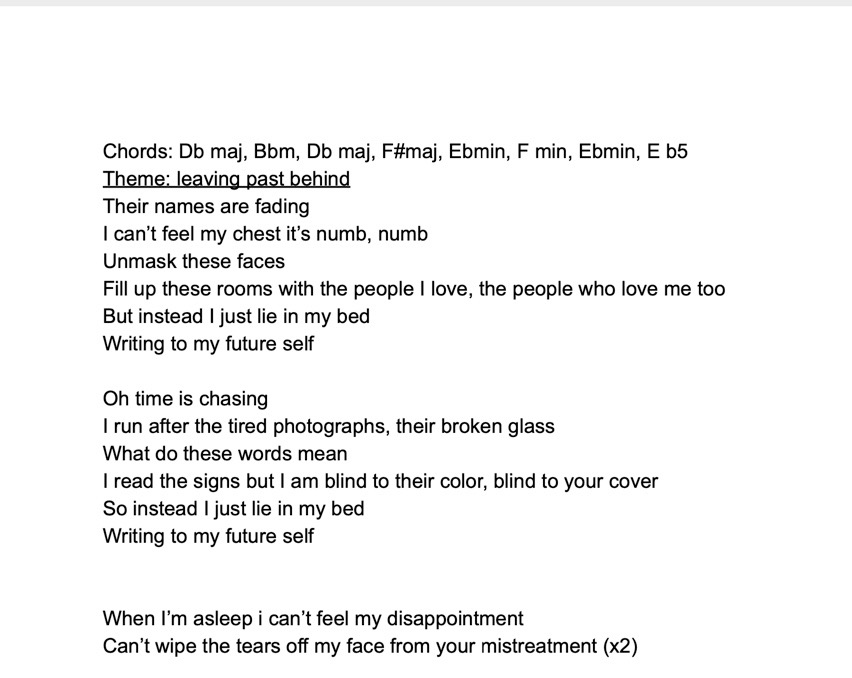

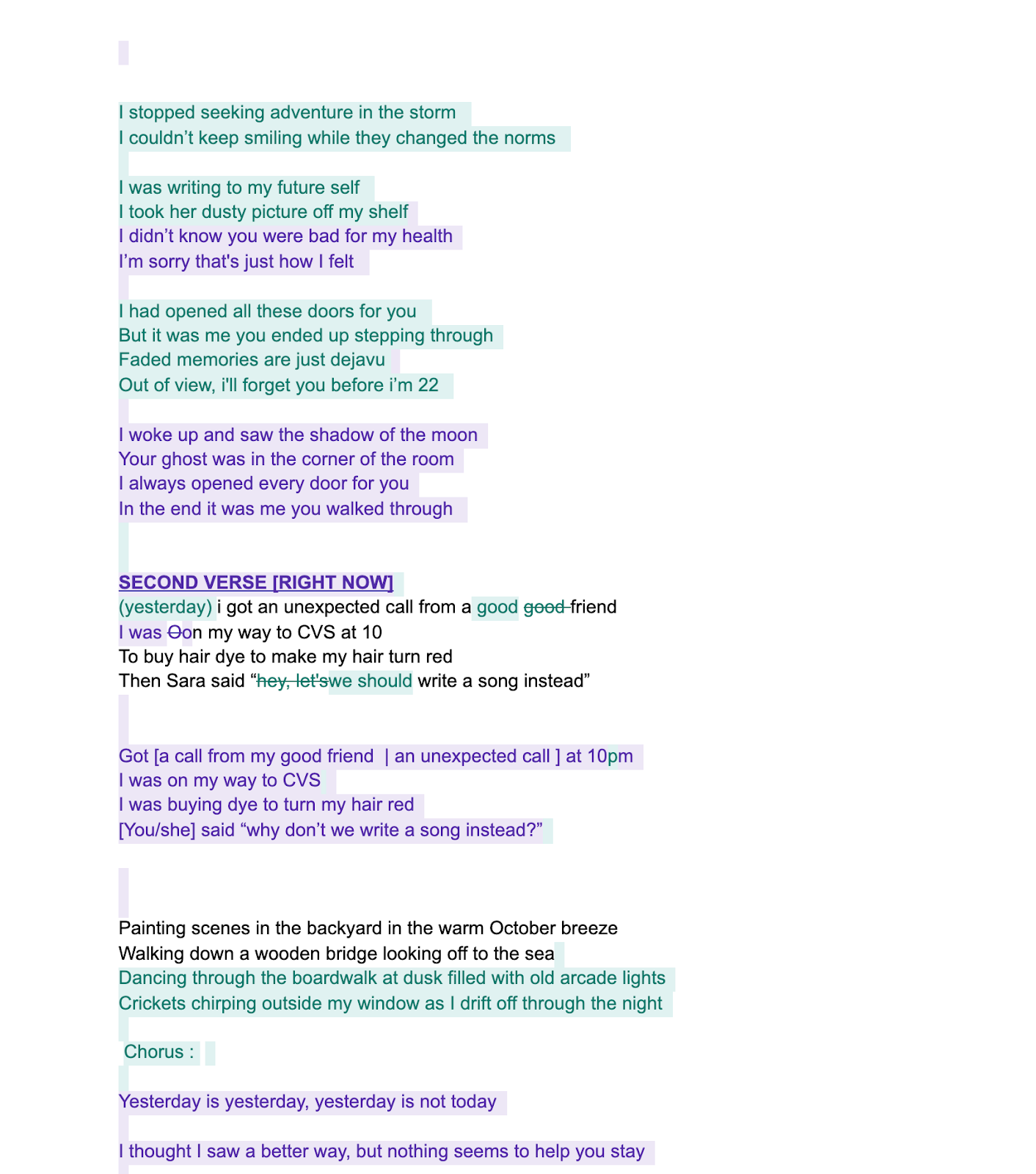

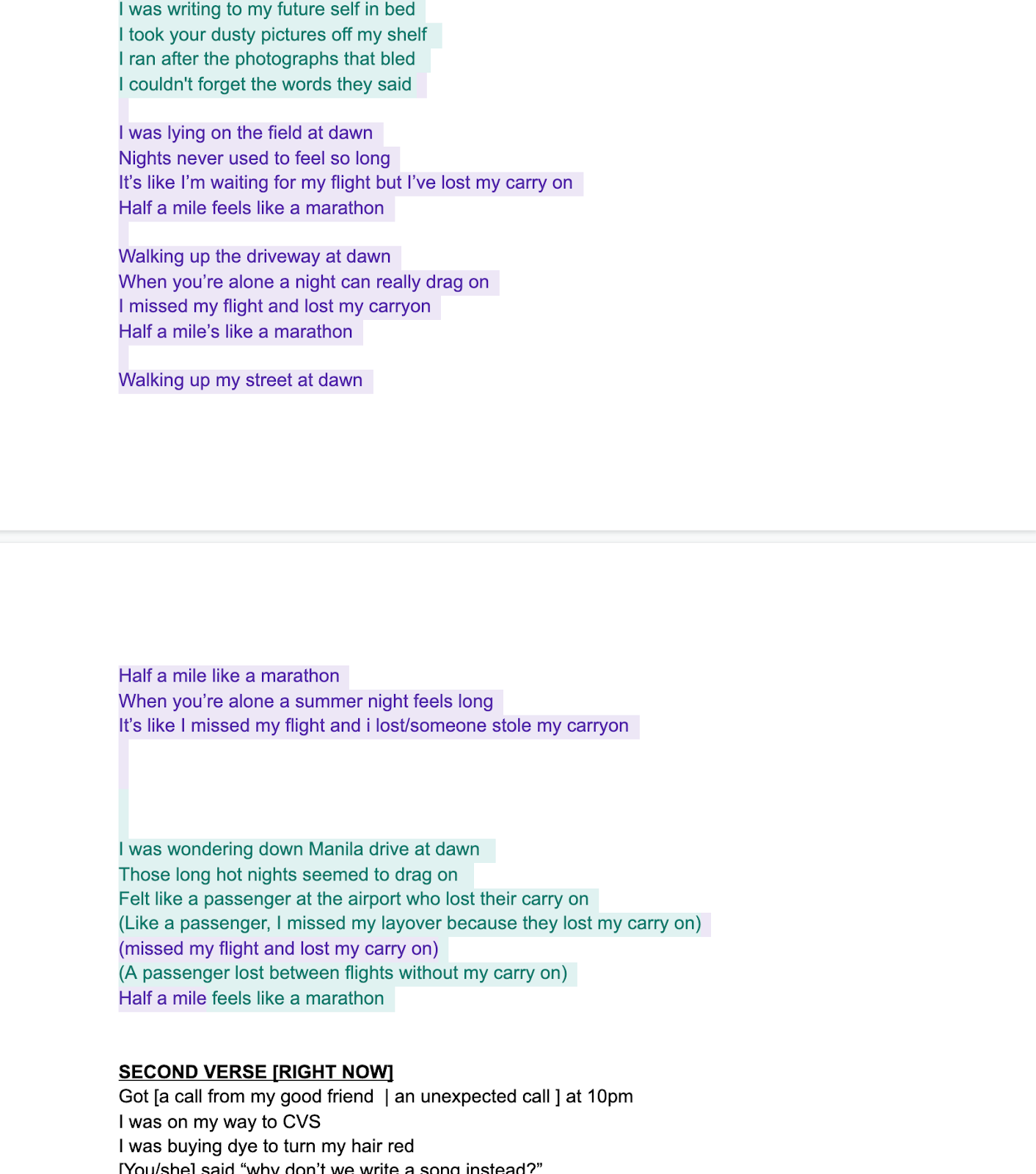

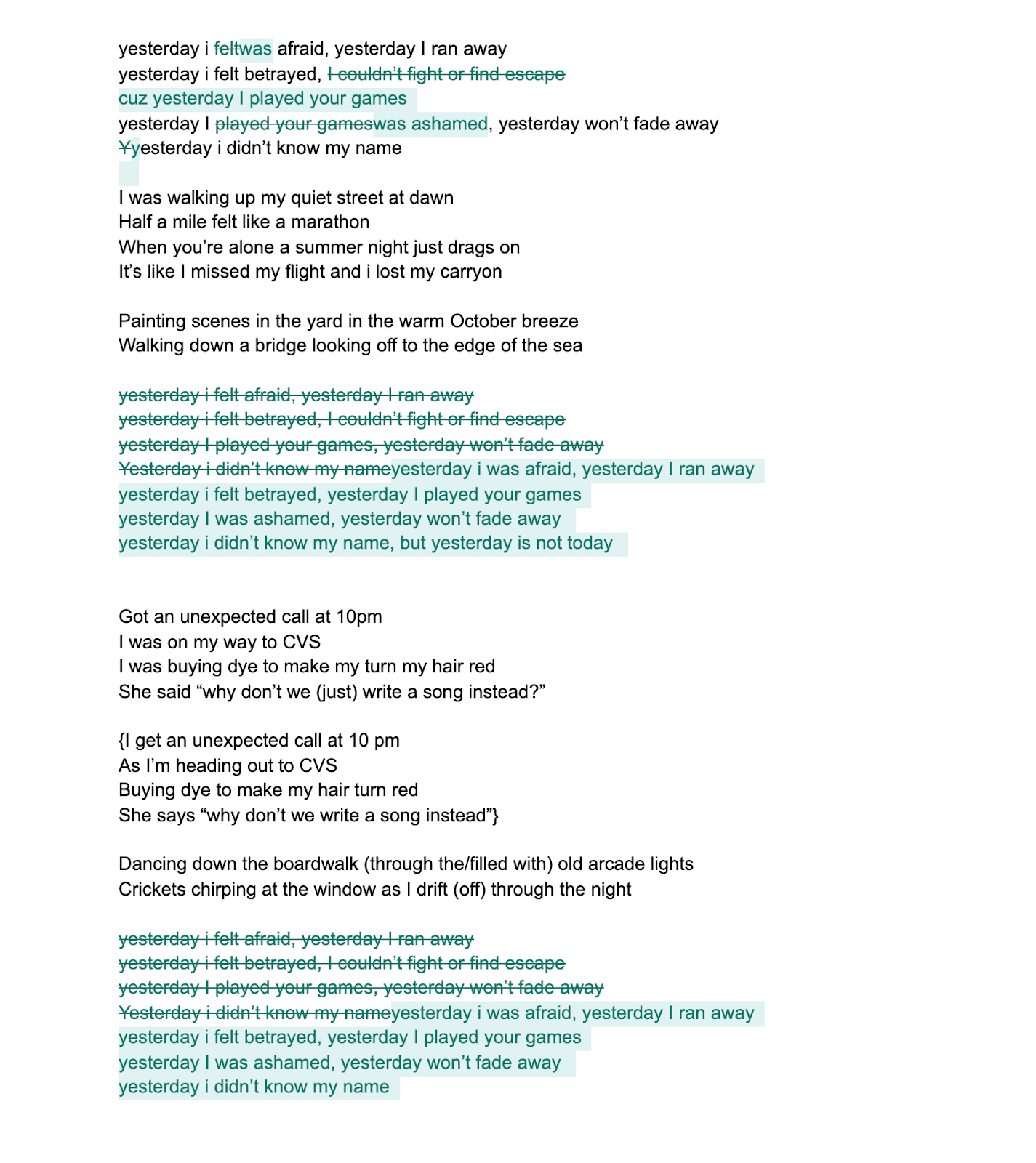

An example of the mess we got ourselves into on what became “yesterday.” A verse that later became part of “strangers” is visible here.

An example of the mess we got ourselves into on what became “yesterday.” A verse that later became part of “strangers” is visible here.

Isabelle had stumbled over and through all of the above in her first attempts at songwriting, but she was struggling with something new as she worked on her first EP. Here’s how she described it to me later:

The biggest obstacle I faced in creating this EP was being able to finish an idea once I started it. Once I was relieved of a particular emotional state, I did not desire to continue writing the lyrics regarding it… I felt disconnected from my work and looking back at the lyrics would make the situation I was writing about seem silly.

We often write best in hindsight. Songs written in the throes of rage or heartbreak can be hackneyed and maudlin as often as they are profound or evocative. Looking back at a turbulent situation, we can observe ourselves with more clarity and articulate the story in a unique way, rather than being overwhelmed by the emotionality of the situation and resorting to vague gestures or clichés and trying to make up for bad writing with good performance and production.

But Isabelle was too detached. She couldn’t connect with the characters in her song, even though some of those characters were her own past selves. That disconnect makes it hard to write anything satisfying or insightful. We get stalled and stuck. It’s not that Isabelle didn’t know how to write. She came up with plenty of ideas every time she improvised or put her pen to paper. The problem was that she didn’t know how to access the mindset that she needed in order to revisit and expand upon her initial ideas. A song or part of a song could be written, but not refined.

Trial and error

I suggested she start sketching out the music, hoping it might spark something and burn through our blockage on the lyrical front. Sometimes, we accidentally sing the line we need, or it pops into our head while we’re working on an arrangement. Sometimes finding the right chord or the right line offers some emotional insight and reconnects us to the story we’re trying to tell. Recording demos of the music unearthed a few more lines of lyrics, but the songs were a long way from finished. You can hear what I mean on this draft of "strangers."

The lyrics still needed tweaking, and we knew we could do better than having her just play chords on the piano. It's a fine demo, but it's lacking the musical polish she was aiming for. Writing for only piano and voice seems like it should be simpler than working with several dozen tracks in Logic, but getting just a voice and a single accompanying instrument to carry the emotional narrative of a song is a major task. It takes time, trial, and a lot of error to figure out how to craft forms and melodies that evoke the vibes you want and keep you hooked into the story of a song from start to finish.

How do you bridge that gap of experience and create something satisfying when you’re still new to a process like songwriting? And how do you reconnect emotionally with experiences that feel remote from your life in the moment, and turn those into satisfying songs? These are the kinds of questions that start popping up left and right when you start aiming higher in your creative pursuits. Isabelle and I had a few weeks to find a way of resolving them, finishing the songs and hitting her self-imposed deadline.

A note about deadlines: Deadlines are healthy. In every creative process, there’s a point of diminishing returns—a point where by continuing to work on the song, we start making it worse, not better. We start to mutilate or twist the song’s best features, add elements that don’t need to be there, or second-guess good ideas.

Beyond that, if your aim is to get better, it’s better to finish more songs than to take more time finishing songs. One of the best things you can do when starting out is to build up a body of work. You’ll quickly improve in some areas, and then notice patterns of stagnation and things to work on in other aspects of your writing.

The best advice I know? Write 100 songs before you assess your skills too intently. Once you’ve built up a body of work and are starting to spot patterns, you can slow down a little and rethink your approach.

Practicing empathy

For the lyrics to work, Isabelle had to grow conceptually. She had to learn to reconnect with and reimagine the experiences she was writing about, so she could spin a convincing and emotional narrative from her current vantage point.

We took time to listen to and analyze songs that blended fiction with personal experience to varying degrees. “Scott Street” (Phoebe Bridgers) provided an example of a songwriter making a composite of experiences that belonged to them and to others, filling in gaps with imagined details or situations, and weaving them into a coherent narrative about heartbreak, loneliness and the alienation of getting older. "Future 500” (Everything Everything) showcased a more radical approach, writing from the point of view of a fictional terrorist agent attacking Buckingham Palace to explore the perils of individualism, inequality, and free will (or the apparent loss thereof).

The freedom of imagination and ability to connect empathetically with others (even those with wildly different motives or beliefs from our own) that Bridgers and Jonathan Higgs were exercising in their songs would be key for Isabelle in reconciling her past and present states of mind and re-accessing the material she wanted to write about.

I asked her to do timed free-writing from the perspective of objects, places and characters. How does a leaf see the world? What does it think about? What are its problems? What about the hills behind her house? Or what about other people? The young girl who lives next door, the old woman at the grocery store, the other people in her songs? What do they see, hear, and feel? What kinds of human connections can we make with people and things that are radically different from us?

We also spent time rethinking the core ideas of each of her songs, and Isabelle scanned her personal history and stories she knew for connections. Rather than trying to report about a single event, she started weaving in memories from other times and fictional imagery to elucidate the central emotions and sentiments of the song.

This allowed her to write in service of the song itself and the tone she wanted to convey: to state her truths, rather than simple facts.

Don’t explain

As ideas started flowing again, we got more hands-on, and adopted a collaborative approach to the lyrics and music. We’d spend lessons co-writing, with long stretches of silent writing punctuated by discussion about a particular line or section, followed by bursts of furious editing, combining and reordering material to integrate it into the song. We adopted a similar approach with the music: I just acted as a producer would, coaching Isabelle and playing or singing suggestions to her as she recorded, either on Zoom or through back-and-forth voice memos.

Working on ideas for “yesterday,” each of us writing ideas for verses and looking for connections or ways to combine our best lines.

Working on ideas for “yesterday,” each of us writing ideas for verses and looking for connections or ways to combine our best lines.

The lyric for “yesterday,” starting to take shape.

We passed the song back and forth, editing and reworking it line by line as the melody developed

The lyric for “yesterday,” starting to take shape.

We passed the song back and forth, editing and reworking it line by line as the melody developed

What we were doing at this point is sometimes called scaffolding, and it’s the bread and butter of learning skills like songwriting, composing and improvising.

The most important lessons in music can’t be explained in a YouTube video. We learn them with our ears first, then our bodies, and later our minds.

We have to hear and feel sounds, trust intuition, and learn by doing, imitating and incorporating sounds and technique into a personal means of expression, the way we learn our first languages. Working on a project side-by-side with a more experienced musician allows you to observe and absorb their approach. You learn to do things that are impossible to teach by explanation. The arduous trial and error process of creative work is guided by your attempts to work with your collaborator, providing a sort of built-in navigation system. It’s a little like being guided through a huge, unfamiliar forest by a parent or older sibling.

Painters during the Renaissance used to learn by assisting their masters, helping fill in details or scenery for larger works. Jazz musicians in the 40s learned a lot of their craft on the job, gigging or recording with older musicians who saw potential in them. Composers in the classical era were known to sit around copying out scores they were interested in. Some, like Mozart, wrote their early works with heavy editorial aid from musical parents. Songwriters write and write, and then they bring their songs to their writing group, their mentor, their band or their producer. As we learn how to fit in and contribute to these different collaborative dynamics, we gain confidence and skills that would take years longer to develop in isolation, if they ever developed at all.

Isabelle thrived on the collaborative dynamic, and we rapidly pulled together three songs, which she released as her first EP, plain sight, at the beginning of 2021.

Looking back

This project was a quantum leap in Isabelle’s writing process, and in her relationship with music.

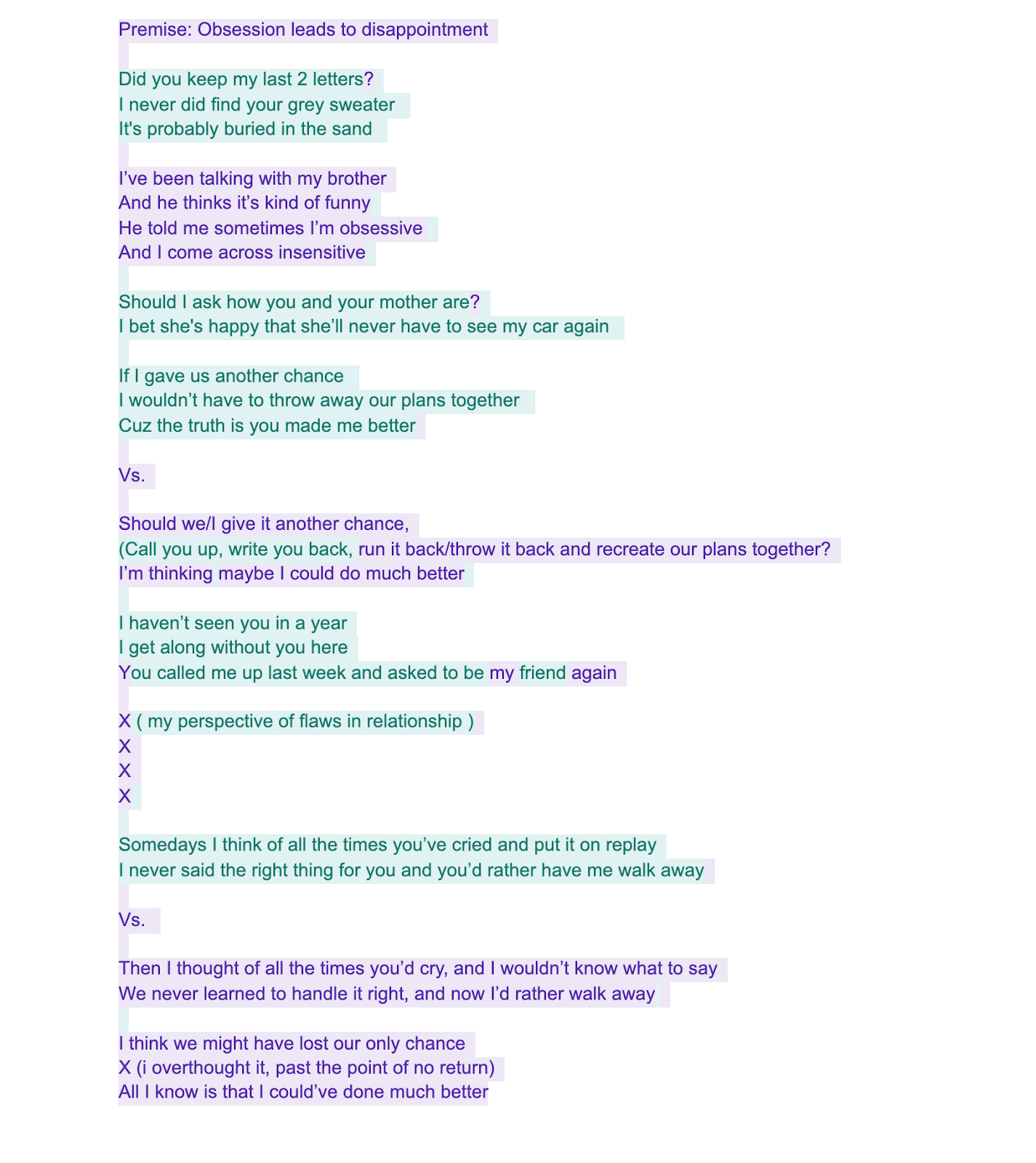

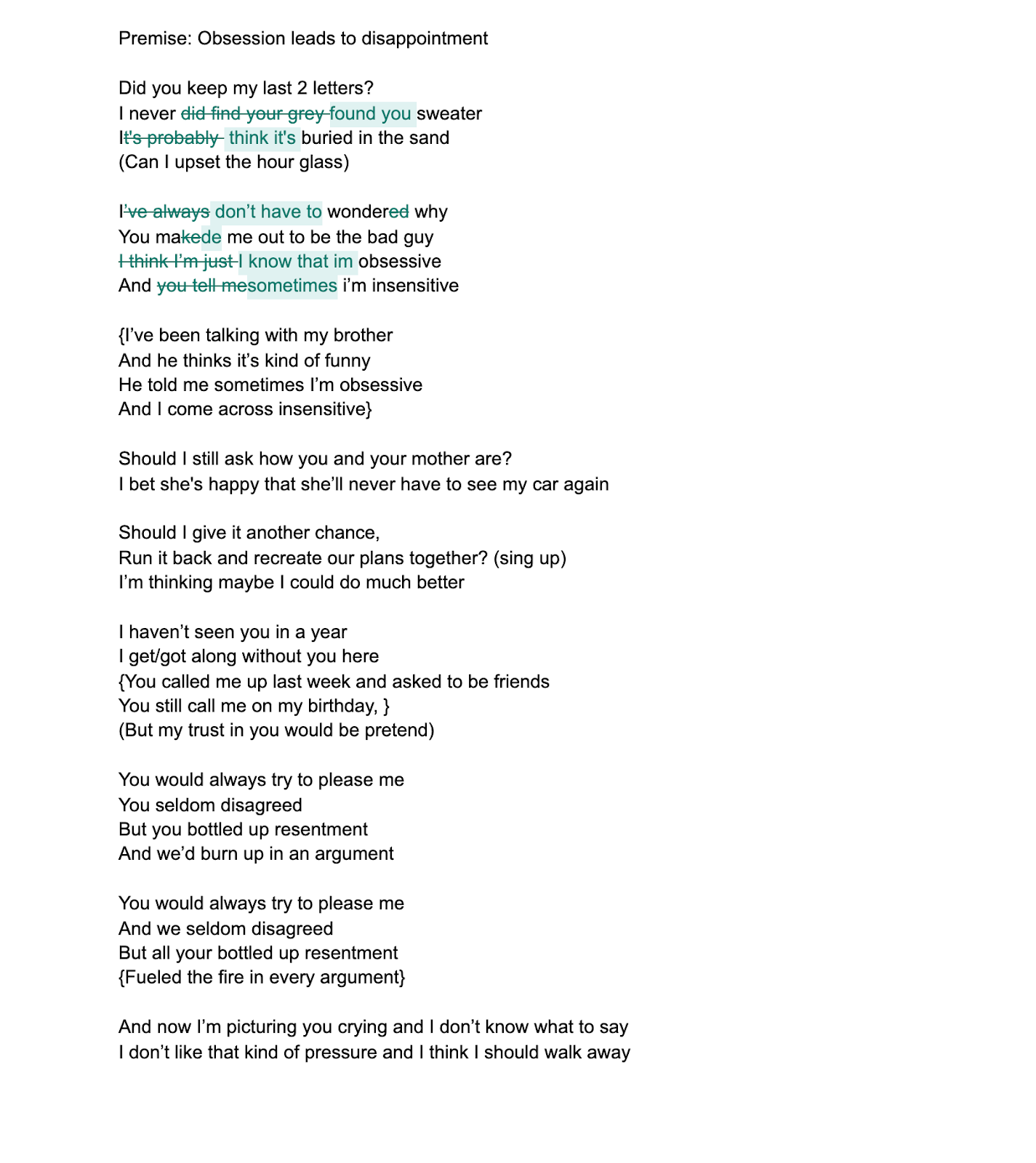

The next lyric we worked on together, “better,” formed mostly in a single smooth cowrite.

From a messy draft on a notebook page...

From a messy draft on a notebook page...

To a quick and smooth cowriting process…

To a quick and smooth cowriting process…

And only a couple drafts later, we were done

And only a couple drafts later, we were done

Her singing matured. She started making more intentional decisions about melody and timbre, injecting emotion into the lyric. Her songs began to have a deeper impact on me as a listener. She stepped more fully into a collaborative relationship with me, which is the best way to learn the ins and outs of any kind of creative music. Rather than me explaining, we spend more and more of our time writing and discussing.

When I asked her what the biggest change she’d experienced musically in the past year was, she told me:

“I see myself as a songwriter now! I used to just think of myself as a pianist... When I look back at ‘find me,’ I’m like, ‘What was I doing? Yikes…’ but I really like this EP. I like these songs.”

She gained confidence and skill as a writer, a singer, and a composer, and plans to continue working on songs for the rest of her life. And that's just from writing three songs—imagine what happens after 100.

Key takeaways

Isabelle’s experience isn’t unique. Anybody with a creative impulse can eventually arrive at songs they love. What’s remarkable is how quickly she did it, but her success isn’t a mystery. Here’s what Isabelle did right:

She didn’t settle

Once she’d written one song and gotten a taste of the songwriting process, she quickly committed to another project that would demand more of her in both the quantity and quality of songs.

She was reflective and open-minded

Isabelle thinks hard about music and about what her teachers and peers say. She was able to articulate her challenges to me with enough clarity that we could find solutions. As students of music, we can’t be passive and expect our teachers to tell us exactly what to do. The question music poses is way too open-ended for that. We have to actively go after what we want and take responsibility for our own learning.

She committed to the work

Isabelle jumps into things with both feet. When I asked her to brainstorm ten lyrics in a week, she did. When I asked her to record and send me parts for a song, she did. There were periods where she spent hours working alone for every hour we spent working together. There is no silver bullet. Sometimes a song seems to write itself, other times it’s a major struggle. What matters most is the attitude we show up with. My first great teacher, Dann Zinn, used to demand an insane amount of practice from us. How we sounded in any given lesson was secondary to the question, “How much did you practice this week?” He was very clear that getting where I wanted to go was a long haul, and he emphasized commitment to the process above all else. Even though I wasn’t happy with how I sounded for many years, I eventually got a lot of joy out of practicing for hours each day. The first step to music you’re proud of is a commitment you can be proud of.

She owned her role

Tying this all together was Isabelle’s way of showing up as a collaborator. Like my own best teachers, I believe in teaching by example and by dialogue. As students, we mostly reap what we sow in those types of relationships. We thrive as students when we take initiative, while remaining flexible and open to coaching. The more Isabelle offered up in terms of ideas, the more I could offer her back in terms of questions and suggestions. And the more active a role she took in shaping the music, the more confident she became as a collaborator. It’s a virtuous cycle.

Making better music isn’t easy, but the process is simple: commit to the work, find people you can trust, and make music with them.

Musicians thrive in dialogue with our teachers, friends, and mentors. Seek out those people and work hard with them. It’s not as simple as following rigid instructions or as easy as watching more YouTube videos, but it’s a lot more satisfying, and if you want to make creative music, it’s the best way forward.

If you want to take on a project like this, or if you're working on one already and need some help, you can send me an email me at ethan@ethanheyenga.com.

Even if you're not sure where to start, that's ok. We'll talk about your musical goals and figure out the next step you need to take.

That's all for now.